October 22

Goodbye to Cairo, it’s good to be Home!

Left to right: Mona, Mabrouka, Kamal (front), Nick (baby), Samy, Nabil and I

We go from a still image in the early sixties to an AI generated, freak me out video. This was created by one of my brother’s colleagues. Nice to have momento.

Egypt as I saw and remembered it

It’s taken me a month to decide what to write about the final two days in Cairo. I was genuinely concerned about how I would portray Egypt, my personal experiences, and life there overall. I held back some observations because I was busy with the day’s activities, but now, since this might be the last article I write, there are too many things I want to share. Sorry to those who wanted just a brief overview; today’s post is not brief. You’ve been warned.

Heck, I haven’t even gone through all the 18,000-plus trip photos once.

I will be jumping around quite a bit in this post; it’s a stream of consciousness that has kept me up at the keyboard for 2 to 3 hours in the middle of the night over the past 3 nights. Let’s start with my experience. Growing up as a Kerba in a household where Sami and Lucy served as role models, I faced significant challenges. Egypt is a country of extremes—both good and bad; the rich and the poor; ancient and modern. It constantly challenges you, regardless of your needs or expectations. That meant I had to make decisions on my return trip, balancing quality and value. That’s nothing new.

The National Museum of Civilization is the new home for mummified Pharos

Ashraf, Tour guide extraordinaire

As travellers, Donna and I have experienced nearly the full spectrum of pricing and service levels. We’ve stayed in places where I was hesitant to even take my shoes off in the room, let alone in the shower. We’ve also been in expensive castles and gone on high-end tours. Our safari was considered a luxury trip, but even then, our room options were high-end but not extravagant. We never stayed in the absolute top-tier rooms, such as those at the Four Seasons or other high-end boutique hotels, at the five-star luxury level. During my research for this article, I found rooms in Cairo costing between US$17,000 and US$21,000 a night. In Luxor, we could have stayed at the same hotel as Agatha Christie did, but at US$1,700 per night, it was over the top for us. We ended up at the New Memnon hotel, a small inn across from the Colossus of Memnon, and made a fantastic connection with the owner, Sayed.

Our goal has always been to seek quality at a good value within our comfort zone. On this trip, I must acknowledge the effort Monique put into making it such a success. She is truly a world-class trip planner. I am known to be a control freak. Usually, it would be very hard to relinquish that control and let someone else organize a trip like this. Monique and I have planned trips together before, and we were so in tune that it made it easy to let go of total control this time.

Our last two days were in Cairo, in Heliopolis, also known as “Masr El Gedida”. Heliopolis was the original “City of the Sun” in 1905. It was built on the outskirts of Cairo as a home for the more affluent. It was inspired by European architecture. Baron Empain was the planner, and his palace has been featured in this blog a couple of times. “Masr el Gedida” literally translates as “New Egypt”.

Arch Angels Greek Orthodox Church of Heliopolis

Arch Angels Greek Orthodox Church of Heliopolis

Sami and Lucy Kerba were married here, and I was christened.

We stayed here intentionally because this is where I was born, where my parents and grandparents lived, and where some passed away — generations of Kerba’s lived and died here. There are cemeteries to visit, churches where my parents married, and where I was baptized. This is also where we celebrated Palm Sunday processions. It was home for the first decade of my life. To Monique’s credit, all of this was driven by her persistence. If it weren’t for her relentless research and efforts, we wouldn’t have seen what we did. My main interests were to see our old apartment and, second, our family church. I would never have been able to see the family church because of fading memories from relatives who were there as adults. All I knew about it was that it was the Orthodox church in Heliopolis.

Oh! How many fond memories were triggered at 11 Roshdi Basha

My new friend, Mahamed Abwa, the Turkish coffee king!

On the first day back in Cairo, Chris joined me on the twenty-minute walk to 11 Roshdi Basha. It was quite an adventure as we ventured alone, without adult companions, to cross the busy streets. Along the way, we stopped at a coffee shop and met, you guessed it, Mohamed, one of the kindest and most gentle people I have ever met in my seventy years of life. We sat down for a cup of authentic Turkish coffee. While Mahamed prepared the coffee, I noticed a framed picture of his family hanging on the wall behind him. I learned that his parents opened this shop in 1952. It was both their business and family home. They used to sleep on a mattress in the middle of the shop, then lift it to the ceiling during the day when the shop was open. The business is open seven days a week for at least ten hours each day. Naturally, I took a picture of him with his family portrait proudly displayed behind him – yes, the focus wasn’t on Mahamed, but it was perfect to showcase the family he was so proud of. Mahamed was also proud of his daughter, who is about to graduate from law school. I plan to reach out to her after this article is posted. I want to let her know that I am featuring her father as one of my favourite people I've met. I will highlight him in my next book, “The Passion and Purpose of Ordinary People.” The coffee cost 25 Egyptian pounds, or 75 cents Canadian. I tried to give him a tip, but he was too proud and refused it, saying it was his honour to serve me.

Fortified with Turkish coffee and preparing for our upcoming challenge of crossing roads, we headed to our destination. Pfft, it was like a walk in the park. As it turned out, the trick was to be part of the car-pedestrian dance. The ultimate trick was to keep the flow going. We only walked along the big boulevard and only had to navigate one major thoroughfare crossing. But by then, we were street-smart and handled it at low-traffic points, breaking it down into manageable segments.

We reached the apartment, and as I approached, distant fond memories started to surface. I first remembered the ice cream shop Uncle Mounir, Monique’s father, would take me to, where I would drink my favourite beverage ever – “Laban mossaqah” (sorry, that’s the closest I can get to phonetic spelling of the name as I remember it). It was most likely a vanilla milkshake, but it remains my favourite.

Then I showed Chris the spot where I would go with one of our servants, Mohamed, to see the guy who laundered and ironed my dad’s shirts. I was genuinely captivated by the man ironing shirts as he heated the iron on something behind him. The impressive part was how he put water in his mouth and sprayed it onto the shirts just before the hot iron moved across the fabric. It was a sight to see. Remember, I might have been five or six years old at the time. I was so impressed by the fine spray that I practised it in the bathroom at home, as none of the killjoys back home would let me iron anything — it was spray. Mohamed was my first great buddy and companion on my outings; likely a teenager then, he was working as a server or errand boy for my mother.

Mohamed would accompany me to the store around the corner and carry the money; I would essentially pick whatever I wanted, and he would pay. I don’t remember ever carrying cash in Egypt. In fact, my earliest money memory was from 1964, when I was ten years old, on our way to Canada. In London, England, I was trusted to go down to our hotel lobby and out to the attached store next door. I was given a variety of coins, and at that time, it was not the decimal system – it was pounds and shillings. Dad explained what each was worth. I tried to remember them, but when I picked up the can of corned beef, the one in the square tin, and took it to the front, I looked at the coins in my hand and quickly forgot their values. I had to rely on the merchant's honesty, who counted the change out of my hand and showed me the value of each coin. To this day, that important moment in my life has shaped how I deal with people—trust is essential to me. I trust too easily, and if you need that extra little bit and take advantage of me, you must have needed it more than I did. Enjoy it, but it will be the last time we do business.

I would periodically be asked to go to Mohamed and wake him up. It was a small hole in the wall, just big enough to fit a single mattress. At the time, we had three servants, Mabrouka, Hassan and Mohamed, each with a variety of tasks that Mom, as the house supervisor, assigned.

As we reached the apartment, we came to a gate. Once again, Chris pushed me, and I was fine seeing it. He wanted me to have more. What came next was nothing short of magical. More memories came back – like the one of me riding on a tricycle on the front balcony mere feet from where we stood.

While I was regaling Chris with stories flooding my mind, a young woman entered the courtyard. I once again recounted the story of my birth in 1954 and my first 10 years in that apartment. I told her how we emigrated to Canada and that this was my first visit back. By now, with the repetition, I’m sure Chris had heard it so many times he could tell my story in Arabic. She couldn’t let me in but relayed the owner's name and phone number.

I reached out to the owners, Jirair and Sossy Hagopian, over WhatsApp, and Sossy replied a while later. By then, we headed back to McDonald's, where we bought Donna a coffee (You’ll need to ask her about her morning coffee routine; I’m not brave enough to put it on public display). She listened to my story and said she would come over next week. I told her we were flying the next night. She replied that she could accommodate us the next day.

We returned the next day, and her husband greeted us. Sadly, Jirair couldn’t let us into the actual apartment but showed us the third-floor unit with the same layout. It was fantastic. I had drawn the layout the night before to prove to Donna and Chris that I could still remember it all these years later. True to form, I was 100 percent accurate. I don’t know why I remember these things and forget what Tylenol is for; it was dead on and almost to scale.

The layout I drew the night before. I just noticed this a month later - note in the description of the balcony, I wrote “balcona”. Instead of “bathroom,” I wrote “hammam.” Both are Arabic words. I must have been thinking in Arabic by the end of the three weeks in Egypt; I never realized I did that until I read this while photographing it for the blog.

As I entered the main door, I recalled other stories as I stepped into each room—like the TV room, where we had only 1.5 channels. I shared a story about my football experience. Football, or as we call it in Canada, soccer, is the national sport of Egypt. We were lucky in Egypt to be among the "haves" in the population. Because of this, we had the very first TV on the block. It was a large console model with a twelve-inch black-and-white TV built into the centre. One afternoon, a big game was on TV. I can't remember if it was an international match or a championship game. It was important enough for Dad to write a note so I could leave school early. When I got home, there must have been 12 to 15 men watching this small TV. The lesson here is that while school is important, some things are even more so; life experiences are worth missing a day for. I can’t remember which lesson I missed that day, but nearly 65 years later, I still remember leaving school to watch the game. Dad understood that balance. Stephen Covey called it “taking time off to sharpen your saw.”

A side balcony was my paper darts balcony. I used to craft special paper darts as ammunition to shoot at the neighbour’s kids on the balcony next door. Most kids would fold the ammunition, but not me; my dad taught me to roll the paper tightly and then bend it. The tighter the roll, the straighter the flight. I also had to make sure I used the right type of elastic to get a better flight; it couldn’t be the flat, wide one — it had to be a round, heavier-duty elastic. I would make bags full of ammo and keep a good supply of fresh elastic bands on hand.

When we entered the kitchen, I told them about the time my buddy Mohammed collected all the shot glasses of Crème de Menthe during a party. When he reached the kitchen, he poured them into a water glass for himself and a small one for little ole me, his best friend. About half an hour later, I was chasing my mother’s best friend and our neighbour, asking her loudly why she was wearing my mom’s shoes.

In the living room, I remembered where the Statue of Venus de Milo sat in the corner; to this day, I still have one of her in our house. I also remember our neighbour, a Muslim, bought a small prayer rug just for me to place beside his, so I could follow him through all the steps of kneeling and praying.

The large bathroom was where my mom set up a still. Yes, you read that right — my mother had a still in her big bathroom in Egypt to make rosewater. It wasn’t there permanently, just for the season. I remember all these contraptions and my mom, dad, grandmother, and Mabrouka watching it drip, drip, drip and discussing how the parts connected. There were a lot of petals.

In our bedroom, I remembered sharing a bed with my grandmother, then Kamal as well. I remembered climbing onto the dresser and jumping onto the bed. I slept in the same bed as my grandmother for the first ten years of my life. I was fifteen years old when Mom and Dad bought their first house, and I had a room to myself.

A large family lived beneath a balcony at the back of the neighbouring apartment. I don’t remember the exact number, but it was likely around eight to ten. They essentially dug a hole under the balcony, surrounded it with canvas, and all of them slept inside. The father looked after the grounds for the building's owner in exchange for the space. I played a game with the children using apricot pits. The game was simple: we took turns dropping two pits towards a small hole in the ground. If you successfully got both pits into the hole, you won them all; if you missed or only got one in, they stayed put.

Mom and Dad would host such large parties that every room—the living room, TV room, dining room, and front balcony—was crowded with people. There was always food leftover at Mom’s regular parties for ten or twenty guests. These leftovers were given to the family next door, with Mabrouka or Hassan, the other two servants who worked for us. She couldn’t be seen personally passing the food, as that might attract many needy people to our door. Instead, she helped directly and almost always anonymously. To this day, I prefer helping individuals directly through random acts of kindness, and I give what I can.

Returning to Egypt on many levels felt like drinking from a fire hose at full tilt. The range of emotions and feelings about the return was sometimes overwhelming; I took a month to write about them. The month away reminded me that not everything is perfect; there is a lot of poverty and many people living below basic income levels, barely able to afford to live, eat, and be good providers. Remember that the person begging you to buy something or for outright cash is merely trying to survive.

Egypt is also a place where a new iPhone might cost the same as in Canada or the US, but here, thanks to our many blessings, it can take just days, weeks, or a month’s worth of work to pay for it. The young server told me it would take him a year to earn enough to buy the same phone. Granted, he is likely on the lower end of the income spectrum, but a year’s worth of life energy in exchange for an iPhone is a tough pill to swallow.

Personal observations on Egypt

The rest of this article discusses Egypt as a country in general, not our specific trip. Feel free to skip it if you're only interested in the trip. However, these are my observations as a tourist connected to the country and its people.

Many people are struggling to make ends meet. For example, I asked a man how he managed to work during the hot summer days in August. The day we visited, it was only 39 degrees. His simple reply was, “It’s my job, I have to.”

If you want a vivid example of Maslow’s “Pyramid of Needs” in real life, just visit Egypt. (Yes, that was intentional.) You see it in the vendor sitting on the sidewalk selling her wares from a tiny box, and at Mina’s House, where the most incredible buffet I’ve ever seen is served, attracting the wealthy. You witness luxury in the US$20,000-per-night rooms at the Ritz on the Nile. True poverty is visible throughout the city and country if you don’t just look but see—the holes in the walls where people eat, live, and pray, and a family of four sleeping in one room. It’s apparent in the ultra-opulent places that most ordinary tourists never even know exist. Or in the airplane passenger, evidently a high-ranking government official, who sat next to Chris and stared at his two phones for the entire hour and a quarter without bothering to engage with the man in the seat beside him. Yes, he’s the one who was greeted by three cars at the bottom of the boarding stairs when we disembarked.

In Egypt, multiple forces are surfacing from various fronts at the same time. Egypt is undergoing change and, in many respects, remains a work in progress. There is a consistent decline, as usual, but also indications of impressive new developments.

There is also plenty of wealth both here and along the route. Money is flowing into Egypt from oil-rich Arab countries like the Emirates, which rebuilt El Alamein. People in these nations still hold Egypt in high regard.

Egypt is truly wealthy; yet it is also poor. The new president, Sisi, is admired by many for his efforts to improve the lives of the country’s less fortunate. Education is free, and military service is mandatory, but the length of service depends on one's educational level. It is 1 year for university graduates, 2 for high school graduates, and 3 for those without formal education.

Schooling, including public universities, is free for Egyptian residents, with the exception of some processing fees, and the right to attend is protected by the constitution. Each August, after grades are registered in a central database, students are ranked. Those with the highest scores can choose which public university and program they want. Students with lower scores have fewer options and may need to pay for private universities, where competition is less intense. Although education is free, children often have to work to support their families. Sometimes, the reward for being good at hustling is enough to make someone a strong provider. This can serve as a disincentive to quit and pursue further education. Maslow’s hierarchy is at play again. Ironically, that was my struggle growing up. I decided to marry early and to be a provider for my family. I left college before earning a degree. Perhaps it was self-esteem or the desire to do better for my family that prompted a career change in my thirties. Maybe that’s why I insisted on taking extra courses to earn credentials that would give me credibility at work. It wasn’t unusual to get 200 hours of continuing education instead of the thirty required by the system. That’s also why I became more involved in associations and organizations, eventually gaining recognition nationally and internationally for my dedication to my profession. Egypt, like everywhere else in our world, faces significant challenges in providing for all its citizens. Its government is continually balancing how and where to allocate resources. Sometimes it seems to be pulling the country up by its bootstraps, but at other times, there is evidence that there are too many bootstraps to lift. It too is overwhelmed by migrants; in Egypt, the infrastructure is stretched on that front.

Egypt is home to the Grand Egyptian Museum, affectionately known as the GEM. It is a project that has taken about twenty-something years and cost over a billion dollars, and it recently opened to the public. It has quickly become the world’s leading museum dedicated to one civilization: Ancient Egypt. The museum houses hundreds of thousands of artifacts and statues, both on display and in proper storage. The entire collection of Tutankhamun’s treasures discovered by Howard Carter is now reunited for the first time in over a century. Egypt also hosts the Old Egyptian Museum in Cairo, which is known to hold various treasures. The entire country is a potential site for significant digs or discoveries, where it seems new finds occur regularly—some buried for centuries.

Decades ago, the United Nations sent a task force to study Egypt to see how they could make improvements. After a couple of years, they realized that they didn’t even understand how it was managed in the first place. But keep going.

Now, entire slums are being demolished, and 351 informal settlements have been identified and targeted by President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and his government since 2014. He aims to eliminate them by 2030. Communities with thousands of residences have been built and are still being developed under this housing plan. These new communities feature subsidized electricity and water, along with sports complexes and parks. People are being resettled—some by choice, some not. Once the slums are cleared, the land is sold to private developers to help fund the construction of the new communities.

Huge sums of new money are constantly flowing into Egypt for both new and, at times, very high-end communities. It was just announced that several Gulf countries and Egypt have signed an agreement to develop projects on the north coast, including Ras el Hekma, a $35 billion, entirely new city on the northern shore of the Mediterranean. The overall megaproject could reach $135 billion. The government hopes to transform its north coast into the new Riviera.

This is the final trip broadcast. Over the next few weeks, I will add three or four photo portfolios as I compile themes. Thank you for joining us on our journey.

When I ask myself whether I truly experienced Egypt or just looked at old monuments and played the tourist, thinking I've seen it.

My answer is an emphatic maybe. In Egypt, it remains both the best of times and the worst of times.

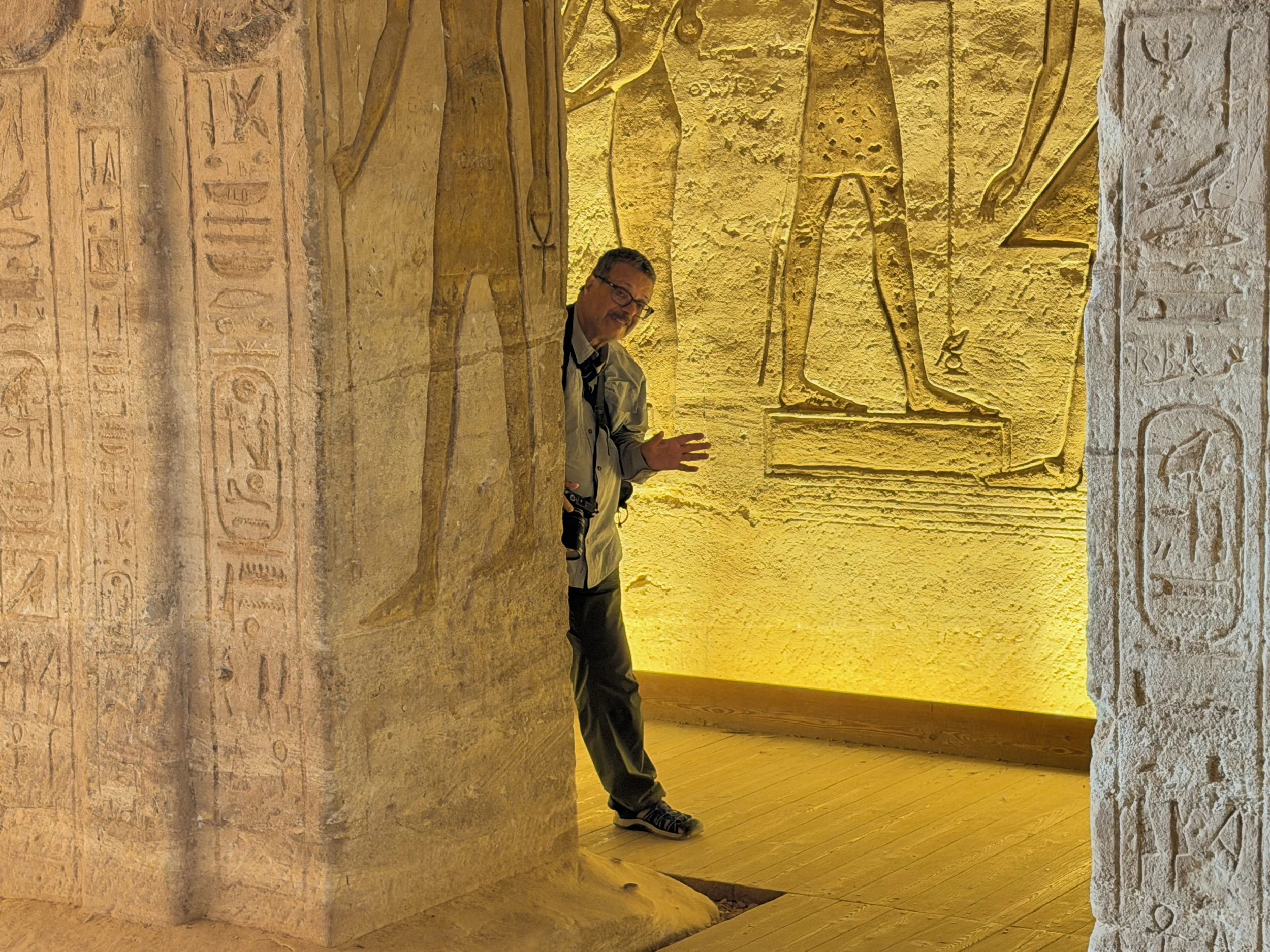

At the old homestead 11 Roshdi Basha

Epilogue and what’s next

Hey, I am retiring on December 31st, and I will likely have a few minutes here and there to revisit this trip. Maybe – I’ve already committed to books two and three, plus I have three other ideas for books percolating. Additionally, I’ve been approached to consider a couple of exciting projects. While I am at it, I’ve decided to start doing portraits and fine art photography again.

Plus, I will finally be able to support my current favourite charities without worrying about influencing clients and risking upsetting regulators.

Honestly, I have no idea what the future will bring, but it will be different and hopefully exciting, that’s for sure.

For now, I will concentrate on promoting Books and photography:

Ordinary People, Extraordinary Lives

https://www.nkerba.com/ordinary-people-extraordinary-lives

2026 Calendar - “Special Places”

Celebrating my blessings of the places I have been fortunate enough to visit.

https://www.nkerba.com/blog/special-places-calendar-2026

Working on interviewing and photographing candidates for the second book:

Passion and Purpose of Ordinary People

Working on interviewing and photographing candidates for the spinoff third book

The Essence of Judo

It's a way of life and not just a sport